Quotations from De Profundis by Oscar Wilde

'I have lain in prison for nearly two years. Out of my nature has come wild despair; an abandonment to grief that was piteous even to look at; terrible and impotent rage; bitterness and scorn; anguish that wept aloud; misery that could find no voice; sorrow that was dumb. I have passed through every possible bout of suffering. Better than Wordsworth himself I know what Wordsworth meant when he said:

'Suffering is permanent, obscure and dark,

And has the nature of infinity.' '

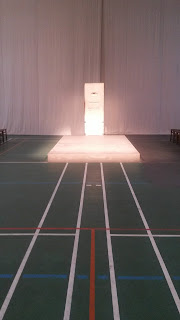

The original door of Oscar Wilde's cell exhibited in the former chapel more recently a rec room at

Reading Youth Offenders'Institute

Stairways at Reading Prison

'To regret one's own experience is to arrest one's own development. To deny one's own experiences is to put a lie onto the lips of one's own life. It is no less than a denial of the soul.'

Abdallah Bentaga - one of Genet's lovers

by Marlene Dumas

Jean Genet by Marlene Dumas

Oscar Wilde and Bosie

by Marlene Dumas

The first set of books sent to Oscar Wilde at Reading Gaol after a new prison governor, Nelson, agreed that he was to be permitted reading material.

A further set of books sent to Oscar Wilde at Reading Gaol

A series of photos taken in Oscar Wilde's former cell

on the day of my visit on 7 December 2016

"Many men, on their release, carry their prison about with them into the air, and hide it as in a secret dialogue in their hearts and at length, like poor poisoned things, creep into some hole and die,'

'I used to live entirely for pleasure. I shunned suffering and sorrow of every kind. I hated both. I resolved to ignore them as far as possible; to treat them as modes of imperfection. They were not part of my scheme of life. They had no place in my philosophy. My mother, who knew life as a whole, used often to quote to me Goethe's lines...

'Who never ate his bread in sorrow,

who never spent the midnight hours

Weeping and watching for the morrow,

He knows not yet, ye heavenly powers.''

'I now see that sorrow, being the supreme emotion of which man is capable, is at once the type and test of great art. What the artists is always looking for is the mode of existence in which soul and body are one and indivisible, in which the outward is expression of the inward; in which form reveals... Truth in art is the unity of the thing with itself.'

'There is before me so much to do that I would regard it as a terrible tragedy if I died before I was allowed to complete at any rate a little of it.'

Reading prisoners in the Victorian age

'There is not a single, wretched man in this wretched place along with me who does not stand in symbolic relations to the very secret of life. For the secret of life is suffering.'

A lithograph of Reading Gaol

Photos around the exhibition

The former cell were prisoners were held

before being sent for execution at the gallows

Me at Reading prison

A poster I found

Photographs by Nan Goldin on the theme of desire,

her boyfriend of the time as the model and inspiration,

shown adjacent to the photograph of Bosie.

her boyfriend of the time as the model and inspiration,

shown adjacent to the photograph of Bosie.

'Bosie'

Random photos from around Reading prison

7th December 2016

Reading The Ballad of Reading Gaol

on the train home

Notes:

When left for the exhibition at the former Reading prison last December, it is honest to say, that my awareness of Oscar Wilde was scant compared with the perception I had as I travelled back home, a train ride, that is, from Reading to London, during which time I read The Ballad of Reading Gaol and began to read De Profundis, the encounter with Wilde at the prison somehow set in high relief against my first experience of his temperament and ideas, as reflected in the words and satire of The Importance of Being Earnest. st as Cecily Cardew in a costumed read through of the performance I remember to this day the exchanges of Cecily and Gwendolyn and considered taking a diary with me to read over on the train in true Gwendolyn style: 'One should always have something sensational to read on the train...'

I had been around fifteen at the time and my mother had provided a Biba Maxi dress she must have bought in the late sixties but with the puffed sleeves and tight buttoned bodice as well as the frills on the hem it sufficed at least to make me feel rather like a Cecily, and I found the irony and elegance of the play rather tantalising, an interest in Wilde at that stage was engendered.

Years later (last autumn in fact) I attended an exhibition at Le Petit Palais seeing the original manuscripts of The Picture of Dorian Gray and De Profundis on display, as well as the controversial calling card of the Marquis of Queensbury alongside notes pertaining to the legal case against Wilde and only then did I really begin too factor the significance of Wilde's imprisonment into my comprehension of this writer's entire oeuvre. By chance, I then read an article about the exhibition I have documented above organised and curated by Artangel, a group that exists to take art into unusual places, and having passed time in the former cell of Oscar Wilde and traversed the grounds into the prison and on exit, I feel I have a measure of comprehension regarding how radically altering his time in such confines must have been, the hooded masks worn on the yards at hard labour, the silence and no eye contact rules, for example. The content of De Profundis is entirely comprehensible in the light of the fact that he was sequestered from the world that he had previously satirised, and he had there encountered such a level of suffering and hardship for the first time, no chance, there of opulence or elegant society.

Out of all the exhibits I think the sculpture, by Jean-Michel Pancin, which includes Wilde's original cell door seemed perhaps the most problematic and perhaps in the light of the way it lodged itself in my mind problematically, intriguing. To my mind the door is effectively re-contextulised here to suggest perhaps a shrine or altar of a kind, the door illuminated in a vast space and raised on the plinth, leading to ideas about the deification, at least the myth-making, surrounding artists and writers.

A further reflection:

"Jean-Michel Pancin has created a poignant sculpture for the chapel: a concrete plinth in the same dimensions as the cells at Reading, with the original door from Wilde’s cell at one end. The door stands in the brightly lit room (one of the building’s less oppressive spaces) as a symbol of confinement, the barrier to freedom that Wilde would have likely stared at for hours on end when denied books and papers." Rachel Steven in The Creative Review

No comments:

Post a Comment